Former Selkirk councillor and local historian Kenneth Gunn attempts to unwind the mysteries of Selkirk's clocks...

THERE has been great anger and humour in almost equal measures recently in the Royal and Ancient Burgh of Selkirk about so-called improvements to the Town Hall and Market Place, which together have left Souters bewildered as to why the changes were made and who is responsible for the short-comings in what was supposed to be an upgrade to the town's heritage.

The first thing that happened was at the Town Hall, which was the home of Selkirk Town Council and earlier was the Courthouse of the local Sheriff, Sir Walter Scott.

A huge underestimate in the costs of restoration saw Scottish Borders Council almost £200,000 short of the cost of repairing the actual steeple of the Grade A Listed Building.

The building has been almost totally ignored since 1974 when the Town Council, and all of Scotland’s town councils, were swept away by a non-local authority system.

What now has taken the place of local government is Scottish Borders Council whose neglect actually led to the enormous costs of repair.

So what did they do and how did the manage to raise the extra capital to finish the works? They applied for further grants and also took an enormous amount of capital out of Selkirk’s Common Good Funds for something that these funds were never intended and all to pay for something which the townspeople had no say in and were not responsible for.

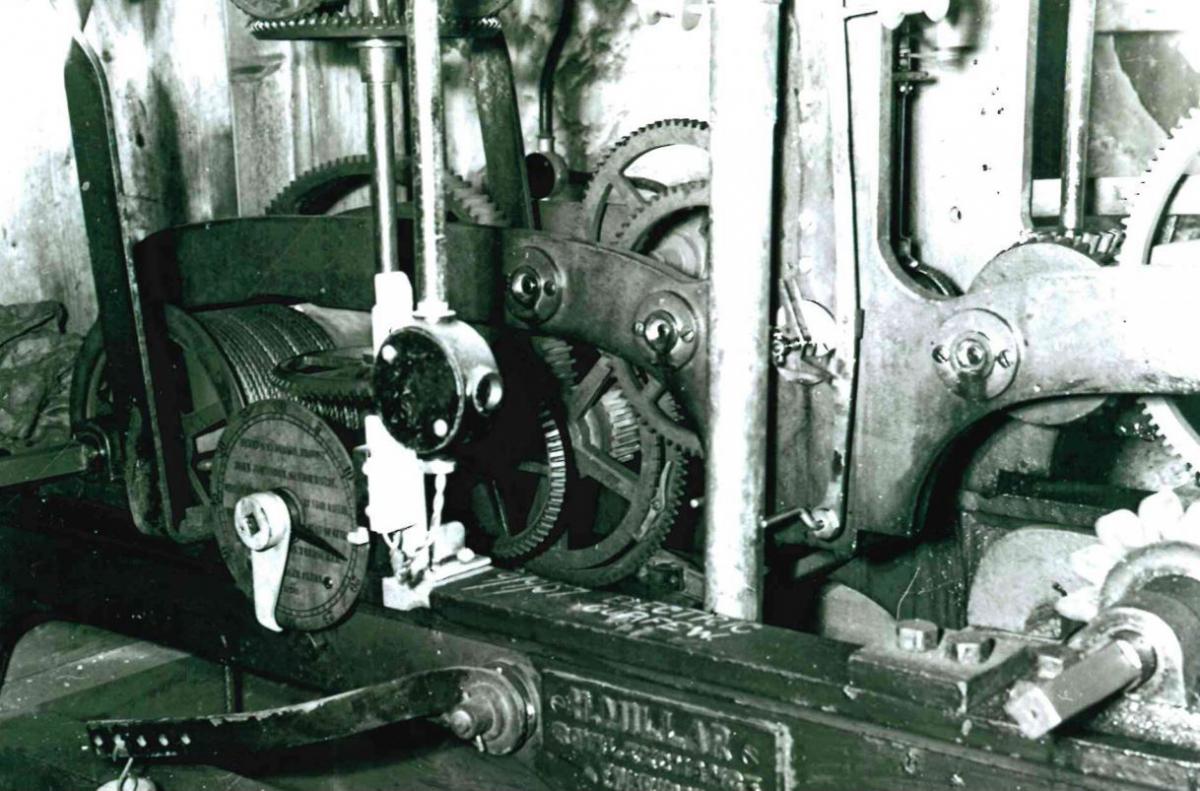

That was the angry part but to counter that there is also the humour to record. It was decided by those in high office that the gold-plated cockerel weather vane should be re-plated and that the Selkirk Town Clock should actually be removed for repair and cleaning. That clock and its illuminated front face were well maintained over many years by local jewellers and clock repairers and in more recent times has been well maintained by Ritchies in Edinburgh without recourse to actual removal from the building.

This time the entire mechanism (or what remains of the original plus its electronic modern wizardry) was lowered by jib-crane and taken on a lorry down to England for a complete overhaul. That was fine and no-one noticed as the whole building was enveloped in scaffolding and plastic sheeting.

However, when it did return and was re-installed in its original place all was not what it seemed.

In fact it has never kept time since it was put back in the Town Hall. Sometimes it simply doesn’t keep time, sometimes it doesn’t go at all and, even worse, it goes backwards!

What happened to the role of Clerk of Works in all this turmoil and who signed off the work which was then proved to be faulty in the extreme with the steeple now leaking water where it had never leaked before and with huge double front doors that after “restoration” couldn’t be opened?

Is Selkirk actually taking a step back in time?

Are our Councillors backward?

Who knows, but come the Common Riding morning let’s hope Selkirk Silver Band big drummer John Nicol has a watch that keeps good time or neither the First Drum nor the Second Drum will ever take place!

But in the middle of all this confusion I have recovered another great mystery, or is it mysteries?

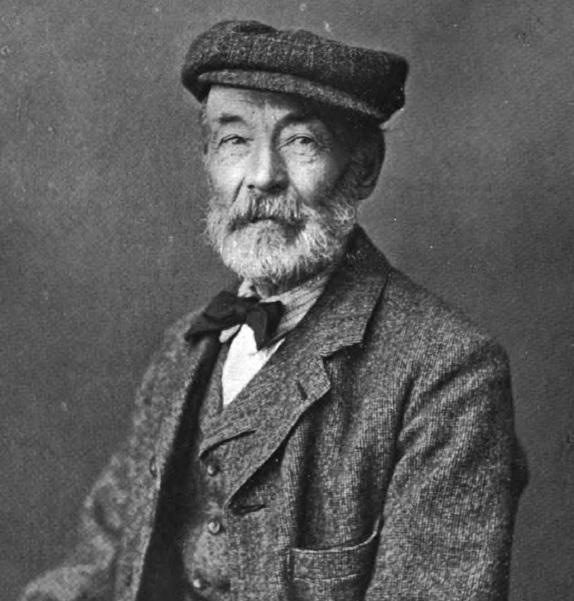

What happened to the works of Selkirk’s mason-astronomer James Scott who was born in Midlem in 1844 and died in November 1928. Who was he and how did he acquire the title mason-astronomer? We have to rely on an interesting little booklet written by Bowmont Weddell, M.A., F.E.I.S and who was headmaster of Selkirk Public School in the 1930s when he wrote and published the pare which was printed by Walter Thomson in High Street.

James Scott was born at “The Burn” in Midlem and followed his father and grand-father into the building trade as a stone-mason after school at Midlem.

His hobby was the repairer of clocks and from that he became a builder of time-pieces and studied not just the time of day but also the universe and how it worked and related to time and movement.

James was totally self-taught but among the books and manuscripts he read was a lecture paper by the City Astronomer of Edinburgh, William Peck. The stone-mason cum clock repairer got even more interested in the stars and planets and their movements to each other and became so knowledgeable that he could predict the phases of the moon and work out on a nightly basis where its place in the heavens would be.

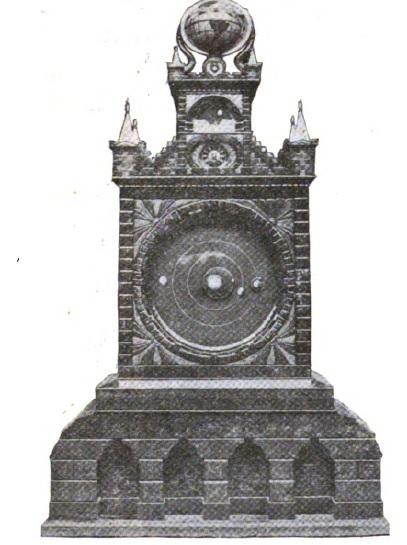

That saw him on a journey in which he designed and built, first of all, his “Great Clock” which told the time accurately while at the same time represent the solar system and the relative movements of the stars and planets around the centre-piece, the sun. Included in this masterpiece are the signs of the Zodiac and through its 365 spaces this Great Clock tells the time, the placings of the planets and a pointer also displays the date and the year.

He developed several clocks, long before the advent of digitisation and modern technology. Some of his works were famous and his Astronomical Clock formed a centre-piece of The Scottish Natural Exhibition in Edinburgh in 1908.

The “Great Clock” and his elaborate but extremely accurate “Jupiter Clock” which spelled out the movement of Jupiter and the rest of the planets in relation to the Sun and Earth, were kept locally and by the date that the Rector of Knowepark Public School, Mr Weddell, wrote his paper in 1935 these valuable inventions were part of the fabric of Selkirk Town Hall, in custody of the people of Selkirk as a tribute and a memorial to a one-time stone mason and self-taught astronomer and clock maker, James Scott.

The question is “where are they now”?

They are obviously parts of Selkirk’s heritage and Selkirk’s past but also a glowing tribute to what can and should be done even today by people with the right attitude to their own environment.

If a tin shed half way down The Green, built as a garage, can in any way be classed as Common Good Property and of any value to the burgh, then all efforts should be involved in finding out where these inventions of James Scott, the Selkirk Mason-Architect are now.

These clocks are certainly worthy of the title Common Good property.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here